This morning, Yahoo!Finance reports that Bloomberg reported that almost $1B has been withdrawn from USO, the biggest U.S. exchange-traded fund that tracks the price of oil, over the past couple of months. The article makes two points that are both interesting and erroneous.

1) The Bloomberg article quotes Bloomberg Analyst Eric Balchunas saying, "The oil rebound has run out of gas and now you are seeing nervous investors with itchy trigger fingers bailing out of USO. They don't want to get burned by another drop in oil".

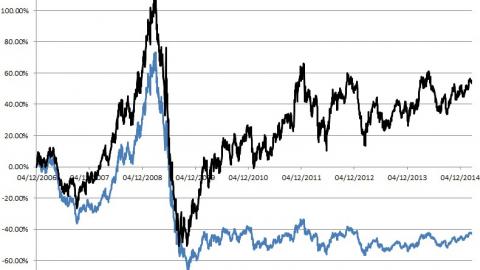

The Truth: Investors are bailing out of USO because its long-term performance is abysmal. As you can see in the chart above, the ETF has sorely underperformed the underlying commodity. The price of oil is represented by the black line while USO is represented by the blue. As of June of last year, USO had underperformed CL by nearly 100%. According to a study done by Yale University called "Facts and Fantasies about Commodity Futures", futures should outperform the underlying not underperform.

2) Funds like USO are "Behind Oil" because the commodity is trading in contango.

The Truth: This statement is completely false. Yes, crude oil is currently trading in a small bit of contango which is what commodities do when they are oversold and set to rebound. But crude oil was trading in significant backwardation last year so futures holders would have outperformed the underlying. According to John Meynerd Keynes and the Yale Study, futures normally trade in backwardation, not contango. And because of this, the long-speculator should on average come out ahead of the change in price of the underlying security.

So what is really going on with USO (and basically all other commodity ETFs and ETNs)?

Several years ago, the SEC passed a series of regulations governing publicly traded commodity pools (i.e. ETFs) and retail mutual funds. The stated purpose was to protect the retail investor but unfortunately the opposite took place. I believe the rigid rules governing these investments allow institutional investors to front-run and free-ride the funds. This provides them with an arbitrage-like gain. Their gain is the fund's lost. For every $1 made in the futures market a $1 is lost so if institutions can game funds like these to their advantage, the fund would find itself at a disadvantage.